Organic vs. Synthetic Fertilizers: A Comprehensive Comparison

Table of Contents

Introduction

The debate between organic and synthetic fertilizers has intensified in recent years as farmers, gardeners, and agricultural professionals seek sustainable yet productive growing methods. Both fertilizer types aim to provide essential plant nutrients, but they differ significantly in composition, production, application methods, and environmental impacts.

Rather than promoting one approach as universally superior, this comprehensive guide examines the nuanced strengths and limitations of both organic and synthetic fertilizers. Understanding these differences allows growers to make informed decisions based on their specific agricultural contexts, soil conditions, crop requirements, and environmental considerations.

This article moves beyond simplistic "natural versus chemical" narratives to provide an evidence-based comparison that acknowledges the complexity of modern agricultural challenges and the diverse needs of different farming operations.

Understanding Both Fertilizer Types

Definition

Derived from plant, animal, or mineral sources that undergo minimal processing and contain carbon-based compounds.

Examples

- Compost

- Manure (various animal sources)

- Bone meal

- Blood meal

- Fish emulsion

- Seaweed extracts

- Rock phosphate

- Green manures

Production Process

Involves collection of organic materials, decomposition, stabilization, and minimal processing. Often produced through natural biological processes.

Definition

Manufactured through industrial processes, containing precise ratios of nutrients in forms readily available to plants.

Examples

- Ammonium nitrate

- Urea

- Triple superphosphate

- Potassium chloride

- NPK blends (e.g., 10-10-10)

- Ammonium sulfate

- Calcium nitrate

- Controlled-release formulations

Production Process

Manufactured through industrial chemical processes, often energy-intensive. Nitrogen fertilizers typically produced via the Haber-Bosch process.

Historical Context

Understanding the evolution of fertilizer use provides important context:

- Pre-20th Century: Agriculture relied almost exclusively on organic fertilizers, crop rotations, and biological processes

- Green Revolution (1950s-1960s): Introduction of synthetic fertilizers dramatically increased crop yields worldwide but created new environmental challenges

- Environmental Movement (1970s onward): Growing awareness of environmental impacts renewed interest in organic methods

- Modern Era: Increasing emphasis on integrated approaches that leverage the benefits of both methods while minimizing drawbacks

Regulatory Considerations

The regulatory landscape differs significantly between organic and synthetic fertilizers:

- Organic Certification: For products marketed as "organic," strict regulations govern approved materials and production methods

- Synthetic Fertilizer Regulation: Focus on safety, handling, and accurate labeling of nutrient content

- Regional Variations: Regulations vary by country and region, affecting what can be used and how it must be labeled

- Environmental Regulations: Growing restrictions on application timing, rates, and methods to minimize environmental impacts

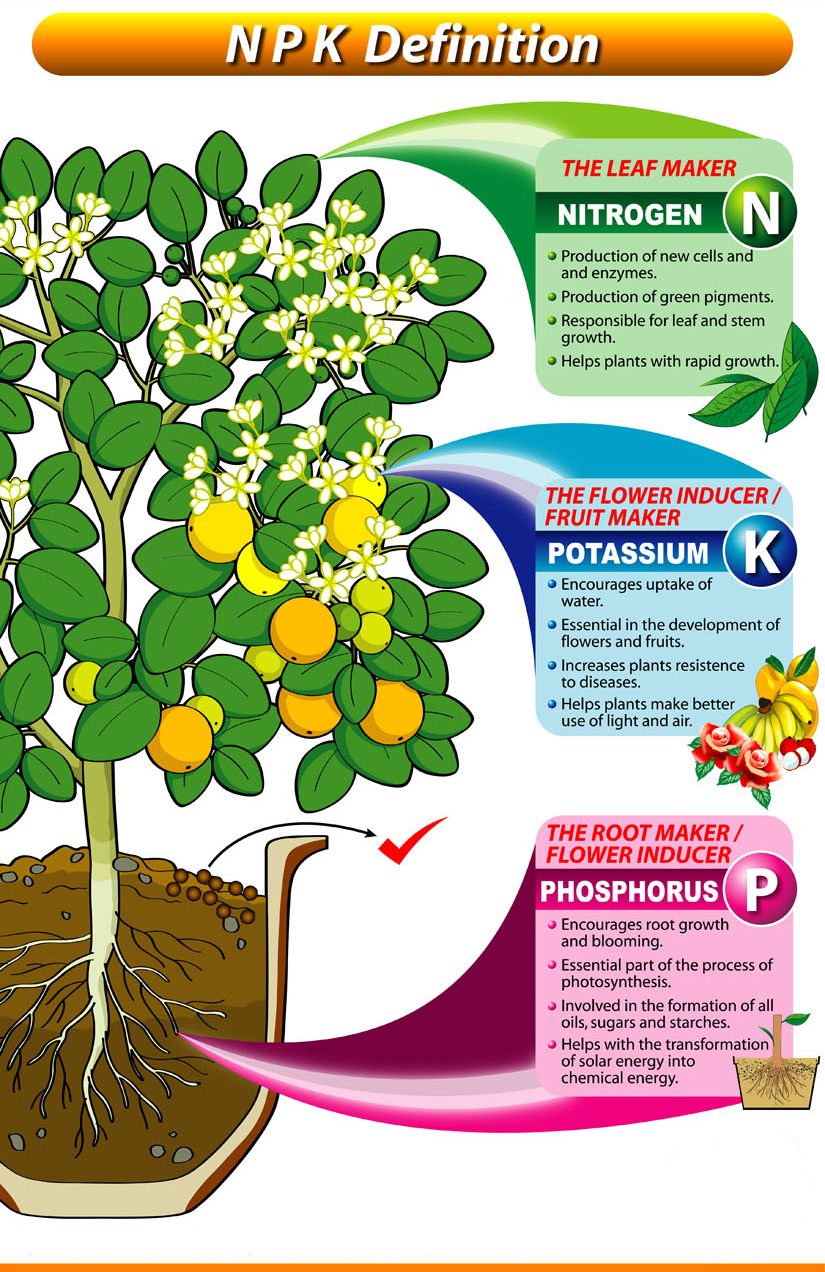

Nutrient Content and Availability

One of the most fundamental differences between organic and synthetic fertilizers is how they deliver nutrients to plants and the timeline of availability.

| Feature | Organic Fertilizers | Synthetic Fertilizers |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Concentration | Generally lower (e.g., compost: 1-3-1) | Higher and precisely formulated (e.g., 20-20-20) |

| Release Pattern | Slow, gradual release as materials decompose | Immediate availability (except controlled-release formulations) |

| Nutrient Forms | Complex organic compounds requiring decomposition | Simple ionic forms immediately available to plants |

| Consistency | Variable based on source materials | Highly consistent and predictable |

| Micronutrients | Often contain trace elements naturally | May need separate micronutrient supplementation |

| Temperature Dependency | Highly affected by soil temperature (requires microbial activity) | Less affected by soil temperature |

Nutrient Release Patterns

Understanding nutrient release timing is crucial for matching plant needs with nutrient availability:

Organic Fertilizers

- Initial Lag Period: Limited immediate nutrient availability as decomposition begins

- Temperature-Dependent: Slow release in cold conditions, faster in warm soils

- Sustained Release: Continues providing nutrients over extended periods

- Variable Timing: Release rates affected by soil moisture, temperature, and microbial activity

Synthetic Fertilizers

- Immediate Availability: Nutrients available as soon as fertilizer dissolves

- Potential Leaching: Risk of nutrients moving below root zone before uptake

- Controlled-Release Options: Special formulations can extend release over weeks or months

- Predictable Patterns: More consistent release rates less dependent on biological activity

Nitrogen Differences

Nitrogen, the most mobile major nutrient, highlights key differences in nutrient behavior:

- Bound in organic compounds (proteins, amino acids)

- Must be mineralized by soil microbes to become plant-available

- Gradual conversion to ammonium and then nitrate forms

- Lower leaching risk due to gradual release

- Release rate difficult to predict precisely

- Available in ammonium, nitrate, or urea forms

- Immediately available or quickly converted to plant-available forms

- Can cause rapid plant growth response

- Higher risk of leaching, especially in sandy soils

- Potential for volatilization losses if not incorporated

Impact on Soil Health

Beyond providing nutrients, fertilizers significantly impact soil physical, chemical, and biological properties over time. These effects can be as important as the direct nutritional benefits to plants.

Physical Soil Properties

| Property | Organic Fertilizer Impact | Synthetic Fertilizer Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Structure | Improves aggregation and structure | Minimal direct effect; potential indirect negative effects |

| Water Infiltration | Increases through improved structure | Little direct impact |

| Water Holding Capacity | Increases as organic matter increases | Minimal direct effect |

| Compaction Resistance | Improves soil resilience to compaction | No significant impact |

| Erosion Resistance | Enhances soil cohesion and stability | Minimal direct effect |

Biological Soil Properties

The soil microbiome plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling, plant health, and long-term soil productivity:

- Provides carbon substrates for microbial growth

- Increases microbial biomass and diversity

- Supports beneficial fungi including mycorrhizae

- Enhances earthworm populations

- Creates more complex soil food web

- Stimulates biological nutrient cycling

- Limited carbon contribution to soil

- Can reduce microbial diversity with long-term use

- High salt concentrations may inhibit certain microbes

- May reduce mycorrhizal associations

- Can create simplified microbial communities

- Potential soil acidification with certain formulations

Chemical Soil Properties

- pH Effects: Many synthetic fertilizers (especially ammonium-based) tend to acidify soil over time, while many organic materials have neutral or alkaline effects

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC): Organic fertilizers gradually increase CEC by building soil organic matter, improving nutrient retention

- Buffer Capacity: Higher organic matter from organic fertilizers improves soil's ability to resist pH changes

- Nutrient Interactions: Complex organic compounds can help prevent nutrient antagonism and fixation issues

Long-term Soil Health Trends

Research studies and long-term trials consistently show divergent effects on soil health:

- Organic Systems: Tend to show gradually improving soil health metrics over time, including organic matter content, microbial activity, and structural stability

- Synthetic-Only Systems: Often exhibit declining organic matter, reduced microbial diversity, and potential structural degradation unless combined with other soil building practices

- Integrated Approaches: Can maintain or improve soil health while achieving high productivity when synthetic fertilizers are used in conjunction with organic amendments and soil conservation practices

Environmental Considerations

The environmental footprint of fertilizers extends beyond the farm, affecting water quality, air quality, and broader ecosystems.

Water Quality Impacts

| Issue | Organic Fertilizers | Synthetic Fertilizers |

|---|---|---|

| Leaching Potential | Lower due to gradual release and binding with soil particles | Higher risk, especially with nitrate forms and in sandy soils |

| Runoff Risk | Reduced with incorporation; potential issues with surface application | Higher solubility creates greater runoff potential |

| Eutrophication Risk | Generally lower but still possible with misapplication | Well-documented risk to surface waters if mismanaged |

| Pathogen Concerns | Potential issues with raw manure; mitigated by composting | No pathogen concerns |

Air Quality and Climate Impacts

Organic Fertilizers

- Carbon Sequestration: Increase soil organic carbon storage

- Lower Energy Inputs: Generally require less energy to produce

- Reduced Fossil Fuel Dependence: Less reliance on natural gas

- Potential Odor Issues: Can produce temporary odors during application

Synthetic Fertilizers

- High Energy Production: Significant energy required for manufacturing

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Substantial N₂O emissions possible

- Fossil Fuel Reliance: Natural gas is key feedstock for nitrogen production

- Ammonia Volatilization: Can contribute to air pollution

Life Cycle Assessment Considerations

Comprehensive environmental assessment must consider the entire life cycle:

- Production Impacts: Synthetic fertilizers have higher manufacturing footprint; organic fertilizers may have collection and transportation impacts

- Application Efficiency: Higher concentration of synthetic fertilizers may reduce transportation and application energy

- Land Use Efficiency: Higher yields from synthetic fertilizers can reduce pressure for agricultural land expansion

- Waste Stream Utilization: Organic fertilizers often utilize materials that would otherwise be waste

Biodiversity Effects

Fertilizer choices influence ecosystem diversity both on the farm and in surrounding areas:

- Soil Biodiversity: Generally higher with organic fertilizers that support more complex soil food webs

- Aquatic Ecosystems: Both fertilizer types can damage aquatic systems if misapplied, but synthetic fertilizers pose higher risks

- Pollinators and Beneficial Insects: Indirect effects through habitat quality and plant health

- Overall Farm Biodiversity: Often higher in organic systems, though this reflects broader management approaches beyond just fertilizer choice

Application Methods and Timing

Fertilizer effectiveness depends not only on what is applied, but how and when it's used. Application methods and timing strategies differ significantly between organic and synthetic options.

Application Methods Comparison

| Method | Organic Fertilizers | Synthetic Fertilizers |

|---|---|---|

| Broadcasting | Common for bulk materials like compost | Efficient for uniform coverage; higher risk of losses |

| Banding | Less common due to bulkiness | Very efficient for row crops; reduces fixation |

| Foliar Application | Limited options (compost tea, fish emulsion) | Wide range of soluble formulations available |

| Fertigation | Limited to liquid formulations | Highly efficient; precise timing possible |

| Incorporation | Often needed to accelerate decomposition | Reduces volatilization losses |

| Precision Application | Challenging due to variable nutrient content | Well-suited to variable rate technology |

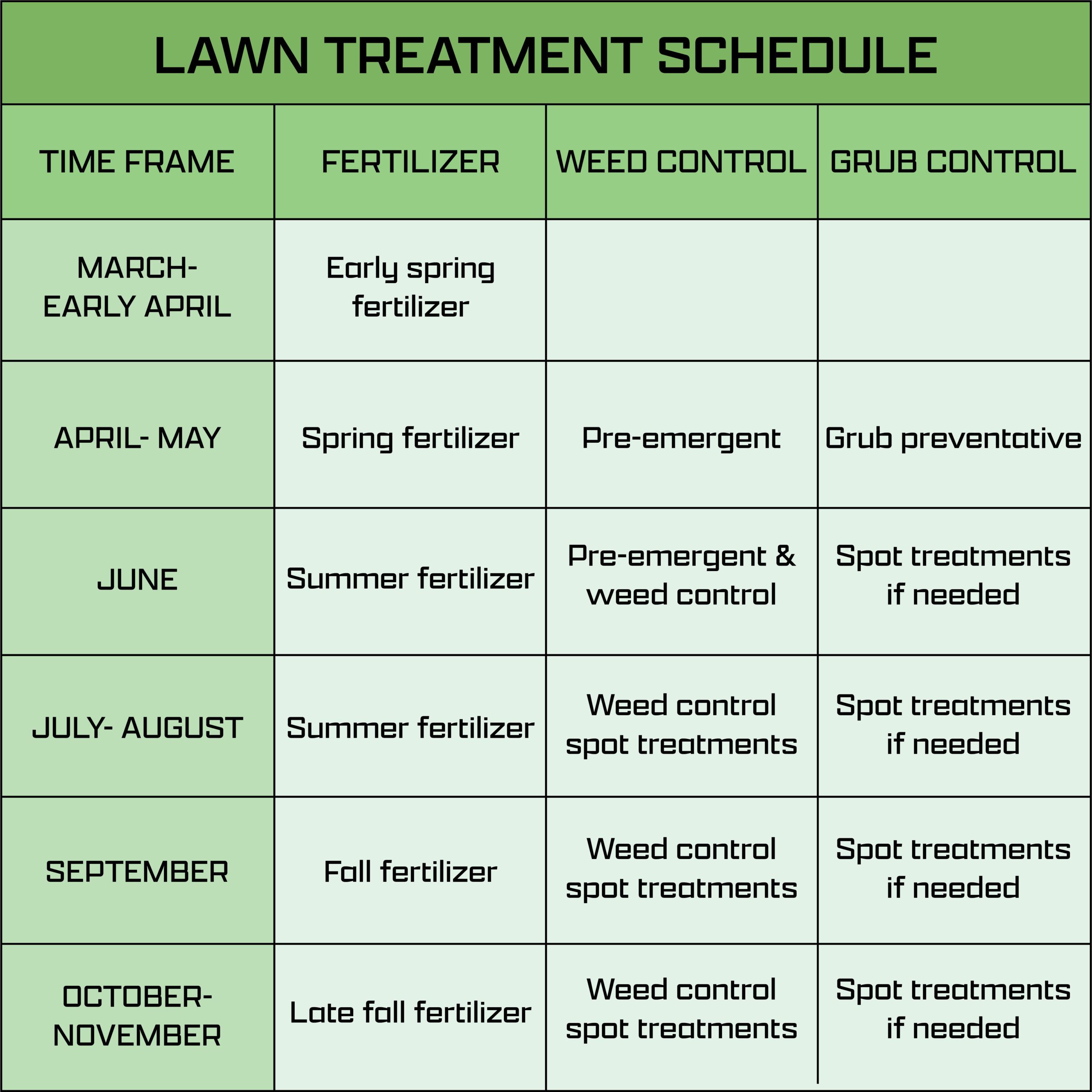

Timing Strategies

Timing fertilizer application to match plant needs is crucial for maximizing efficiency and minimizing environmental impact:

- Anticipatory Application: Apply well before peak nutrient demand to allow decomposition

- Season-Long Strategy: Often focused on building soil fertility rather than meeting specific growth stages

- Complementary Timing: Different materials release at different rates (e.g., blood meal for quick N, bone meal for slow P)

- Weather Considerations: Needs warm, moist conditions for optimal decomposition

- Long-Term Outlook: Building soil nutrient banks over multiple seasons

- Just-in-Time Delivery: Can be timed to align precisely with crop demand

- Growth Stage Targeting: Specific formulations for vegetative, flowering, or fruiting phases

- Split Applications: Multiple smaller applications to improve efficiency

- Weather Avoidance: Application timing to avoid runoff or volatilization losses

- Sensor-Driven Timing: Can be guided by plant tissue or soil testing results

Labor and Equipment Considerations

- Volume Differences: Organic fertilizers often require handling larger volumes of material

- Equipment Compatibility: Conventional equipment may need modification for some organic materials

- Application Frequency: Synthetic options may allow fewer total applications

- Storage Requirements: Different stability profiles and storage needs

- Specialized Equipment: Precision application technologies often more developed for synthetic options

Seasonal Considerations

Different fertilizer types have distinct seasonal strengths and limitations:

- Early Spring: Synthetic options work better in cold soils where organic matter decomposition is slow

- Summer: Both options effective when soil is warm; organic materials continue slow release during hot periods

- Fall: Organic materials can build soil for next season; some synthetic options pose higher leaching risk

- Winter: Limited activity for both; cover crops can capture and store nutrients from fall-applied organic materials

Cost Analysis and ROI

The economics of fertilizer choices extend beyond the initial purchase price to include application costs, yield effects, and long-term impacts.

Direct Cost Comparisons

When comparing costs per unit of nutrient, significant differences emerge:

| Cost Factor | Organic Fertilizers | Synthetic Fertilizers |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Unit Nutrient | Generally higher per pound of N-P-K | More cost-effective per pound of N-P-K |

| Application Cost | Higher due to bulk volume and weight | Lower due to concentrated formulations |

| Labor Requirements | Typically higher | Generally lower |

| Storage Requirements | Greater space needed | Less storage space required |

| Price Volatility | More stable pricing | Subject to energy price fluctuations |

Return on Investment Considerations

A comprehensive ROI analysis must consider:

Organic Fertilizer Value-Adds

- Soil structure improvements

- Increased water-holding capacity

- Enhanced soil microbial activity

- Potential premium prices for organic products

- Reduced irrigation costs over time

- Lower risk of soil compaction

Synthetic Fertilizer Value-Adds

- More consistent yield response

- Greater precision in nutrient delivery

- Lower labor costs per unit nutrient

- Reduced equipment wear

- Simplified logistics and storage

- Better compatibility with precision ag systems

Long-Term Economic Analysis

The economic comparison shifts when considering multi-year timeframes:

- Short-Term Advantage: Synthetic fertilizers often provide more immediate economic returns due to lower initial costs and consistent performance

- Medium-Term Convergence: As soil health benefits accumulate, organic approaches often see improved performance and efficiency over 3-5 years

- Long-Term Considerations: Sustained organic approaches may reduce input costs over time through improved soil function, but require consistent management

- Risk Management: Organic systems often show greater resilience to extreme weather events and input price volatility

Market Considerations

Additional economic factors to consider:

- Price Premiums: Certified organic products can command significant market premiums

- Certification Costs: Organic certification involves additional expenses and documentation

- Transition Period: Converting from conventional to organic often involves yield reductions during the transition period

- Market Access: Different marketing channels and opportunities

- Supply Chain Considerations: Availability, consistency, and logistics differ significantly

Crop-Specific Considerations

Different crops have varying nutrient needs, growth patterns, and responses to fertilizer types. These differences influence which fertilization approach may be more suitable.

Row Crops and Grains

| Crop | Organic Approach | Synthetic Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | Challenging due to high N demand | Well-suited; precise timing possible | High nitrogen requirement; benefit from starter P |

| Soybeans | Well-suited; N fixation reduces needs | Effective with focused P-K inputs | Nitrogen fixation reduces N needs; responds to P-K |

| Wheat | Moderate success with adequate planning | Very responsive to timed N applications | Split N applications often beneficial |

| Rice | Traditional systems often use organic materials | Modern systems rely on synthetic inputs | Flooding affects nutrient availability |

Vegetable Crops

- Excellent for long-season vegetables with continuous harvest

- May improve flavor profiles in some crops

- Reduced nitrate accumulation in leafy greens

- Better suited to direct market and premium markets

- Improved disease resistance in some vegetable crops

- Precise timing for short-season vegetables

- Effective for heavy feeders with high nutrient demands

- Easier to manage for succession plantings

- More predictable sizing for uniform harvest

- Better suited to mechanical harvest timing

Fruit Production

Perennial fruit crops have unique considerations:

- Establishment Phase: Balanced approach needed; synthetic options provide quick available nutrients while organic builds long-term fertility

- Production Years: Organic materials can build sustained nutrition without growth flushes that affect fruit quality

- Fruit Quality Factors: Some evidence suggests organic fertilization improves flavor compounds and storage quality

- Root Zone Management: Organic materials enhance mycorrhizal associations beneficial to many fruit crops

- Long-term Soil Health: Particularly important for perennial systems that cannot be easily renovated

Specialty Crops

High-value specialty crops often benefit from tailored approaches:

- Vineyard Systems: Often use blend of compost for soil health with targeted synthetic nutrients

- Greenhouse Production: Synthetic nutrients dominate in soilless systems; organic options increasing in soil-based systems

- Medicinal Herbs: Often grown with organic inputs to avoid residues and enhance compound development

- Cut Flowers: Blend approaches common, with synthetic for growth and organic for stem strength and vase life

The Blended Approach

Rather than viewing organic and synthetic fertilizers as opposing options, many successful farmers integrate both approaches to leverage their complementary strengths.

Integrated Fertility Management

Key principles of a blended approach include:

- Soil-First Focus: Prioritize building soil health with organic materials as the foundation

- Strategic Supplementation: Use targeted synthetic inputs to address specific crop needs or timing issues

- Monitoring-Based Decisions: Regular soil and tissue testing to guide precise interventions

- Continuous Improvement: Gradual reduction in synthetic inputs as soil health improves

- Context Sensitivity: Adjusting the balance based on soil type, crop needs, and environmental conditions

Successful Integration Strategies

| Strategy | Implementation Approach | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Base-Plus System | Organic materials provide base fertility; synthetic used for specific growth stages | Builds soil health while ensuring critical nutrient timing |

| Transitional Approach | Gradual increase in organic inputs while decreasing synthetic dependence | Minimizes risk during transition to more sustainable systems |

| Deficit Targeting | Organic materials for majority of needs; synthetic to address specific deficiencies | Optimizes nutrient use efficiency and minimizes losses |

| Seasonal Splitting | Organic materials in fall/winter; precision synthetic during growing season | Builds long-term fertility while meeting immediate crop needs |

Case Study Examples

- Vegetable Farm Example: Compost application in fall builds soil; targeted fertigation with synthetic during peak growth

- Row Crop Example: Cover crops and manure build base fertility; precision synthetic application at key growth stages

- Orchard System Example: Compost mulch provides slow-release nutrients; foliar sprays address specific deficiencies

Challenges of Integration

Successfully combining approaches requires addressing:

- Management Complexity: Requires more knowledge and decision-making than single-approach systems

- Equipment Needs: May require different application tools and methods

- Nutrient Accounting: More complex to track total nutrient applications and balance

- Regulatory Considerations: May affect organic certification status if pursuing that market

Decision-Making Framework

Selecting the right fertilizer approach requires systematic evaluation of multiple factors. This framework helps guide decision-making based on your specific context.

Assessment Factors

| Factor | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Soil Characteristics | Current fertility, organic matter content, pH, texture, drainage, microbial activity |

| Crop Requirements | Nutrient needs, growth pattern, root characteristics, quality parameters |

| Climate and Weather | Temperature patterns, rainfall, growing season length, extreme events |

| Management System | Equipment availability, labor resources, technical expertise, monitoring capacity |

| Economic Factors | Market opportunities, price premiums, input costs, cash flow considerations |

| Environmental Goals | Water quality protection, carbon sequestration, biodiversity enhancement |

| Regulatory Context | Organic certification requirements, nutrient management regulations |

Decision Process

- Baseline Assessment: Conduct comprehensive soil testing and crop history review

- Goal Setting: Define clear production, economic, and environmental goals

- Resource Inventory: Identify available organic materials, equipment, and expertise

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate potential challenges and transition issues

- Strategic Planning: Develop multi-year fertility plan with measurable benchmarks

- Implementation: Begin with pilot areas to test and refine approach

- Monitoring: Regular soil and tissue testing to track results

- Adaptation: Adjust strategies based on measured outcomes and observations

When Organic Approaches May Be Optimal

- Degraded soils needing structural improvement and biological activation

- Production systems targeting organic markets or premium prices

- Areas with high risk of nutrient leaching or runoff

- Systems with ready access to quality organic materials

- Perennial crop systems where long-term soil building is prioritized

When Synthetic Approaches May Be Optimal

- Large-scale production with limited organic material access

- Short-season crops requiring precise nutrient timing

- Crops with very high nutrient demands at specific growth stages

- Systems with limited labor or specialized equipment

- Already healthy soils where maintenance rather than building is the goal

When Blended Approaches Make Most Sense

- Transitioning systems moving toward reduced synthetic inputs

- Diversified farms with varying crop needs and rotations

- Operations balancing production, environmental, and economic goals

- Systems with seasonal constraints on organic matter decomposition

Future Trends

The fertilizer landscape continues to evolve with new technologies and approaches that are blurring the traditional divide between organic and synthetic options.

Emerging Innovations

- Enhanced Efficiency Fertilizers: Polymer coatings, stabilizers, and controlled-release technologies that reduce losses and improve timing

- Bio-based Fertilizers: Products derived from biological processes but engineered for specific performance characteristics

- Microbial Inoculants: Specialized microbial products that enhance nutrient availability or fixation

- Nanotechnology: Nano-scale formulations for precision delivery of nutrients

- Recycled Source Materials: Recovered nutrients from waste streams, including struvite from wastewater

- Biostimulants: Materials that enhance nutrient uptake without directly providing nutrients

Evolving Regulatory Landscape

Changes in regulation are reshaping fertilizer management:

- Environmental Regulations: Increasing restrictions on nutrient applications in sensitive watersheds

- Organic Standards: Ongoing evolution of what materials qualify for organic certification

- Carbon Markets: Emerging opportunities for credit generation through soil carbon sequestration

- Water Quality Trading: Nutrient credit trading systems that monetize reduced environmental impact

- Sustainability Certification: Growing influence of broader sustainability metrics beyond organic/conventional divide

Research Directions

Current research focuses on addressing limitations of both approaches:

- Precision Organic Systems: Improving consistency and predictability of organic nutrient sources

- Reduced-Impact Synthetics: Lower carbon footprint manufacturing and enhanced efficiency formulations

- Soil Microbiome Management: Better understanding and manipulation of soil biological processes

- Plant Breeding: Developing varieties with enhanced nutrient use efficiency for both systems

- Decision Support Tools: Advanced modeling for optimizing blended fertility programs

The Convergent Future

The future likely involves greater convergence of approaches rather than polarization:

- Systems Thinking: Focus shifting from product type to overall system outcomes

- Outcome-Based Assessment: Evaluation based on environmental footprint rather than input category

- Hybridized Solutions: Products that combine biological and synthetic components for optimized performance

- Technology Integration: Precision application systems that work with diverse input types

- Circular Economy: Growing emphasis on nutrient recycling and recovery from all available streams

Conclusion

The comparison between organic and synthetic fertilizers reveals that neither approach is universally superior. Each offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be evaluated within the specific context of your farming operation.

Key Takeaways

- Complementary Strengths: Organic fertilizers excel at building long-term soil health while synthetic options provide precision and immediacy

- Context Matters: Soil type, crop needs, climate, and management capacity all influence which approach makes most sense

- Beyond Binary Thinking: The most effective approach for many farms involves thoughtful integration of both fertilizer types

- System Outcomes: Focus on measurable results in productivity, soil health, and environmental impact rather than ideological positions

- Continuous Learning: The science and technology of plant nutrition continues to evolve, requiring ongoing adaptation

By moving beyond the organic versus synthetic debate and focusing instead on evidence-based practices tailored to your specific context, you can develop a fertility management approach that simultaneously supports productivity, profitability, and sustainability. The future of agriculture lies not in rigid adherence to a single approach, but in thoughtful integration of diverse tools and techniques to create resilient farming systems.