Micronutrient Deficiencies: Visual Guide to Identifying and Correcting Issues

Table of Contents

Introduction

While nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium often take center stage in agricultural fertility programs, micronutrients play equally vital roles in plant health and productivity. Despite being required in smaller quantities, these essential elements can dramatically impact crop yields when deficient. The challenge lies in correctly identifying which micronutrient is lacking, as symptoms can sometimes appear similar or be confounded by other stress factors.

This comprehensive visual guide will help you identify and correct common micronutrient deficiencies in your crops. By learning to recognize the distinctive visual symptoms, understanding the underlying causes, and knowing how to effectively address these issues, you can maintain optimal plant nutrition and maximize your agricultural productivity.

Understanding Micronutrients in Agriculture

Micronutrients are elements required by plants in trace amounts (typically measured in parts per million), yet they're crucial for essential physiological functions. Unlike macronutrients (N-P-K), which are building blocks for plant tissues, micronutrients primarily serve as catalysts in enzyme systems and biochemical reactions.

Essential Micronutrients and Their Functions

| Micronutrient | Key Functions | Mobile in Plant | Most Sensitive Crops |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn) | Enzyme activation, auxin production, protein synthesis | Low mobility | Corn, beans, citrus, pecan, rice |

| Iron (Fe) | Chlorophyll synthesis, enzyme systems, respiration | Low mobility | Berries, citrus, ornamentals, soybeans |

| Manganese (Mn) | Photosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism, enzyme activation | Low mobility | Small grains, soybeans, vegetables |

| Copper (Cu) | Enzyme activation, photosynthesis, lignin formation | Low mobility | Small grains, onions, spinach |

| Boron (B) | Cell wall formation, flowering, fruiting, seed development | Low mobility | Alfalfa, apple, brassicas, celery |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | Nitrogen metabolism, enzyme function | Medium mobility | Brassicas, legumes, citrus |

Factors Affecting Availability

Micronutrient deficiencies often result not from a lack of total nutrients in the soil but from conditions that limit availability:

- Soil pH: Most micronutrients become less available in alkaline soils (pH > 7.0), with iron, manganese, zinc, and copper availability decreasing dramatically as pH increases. Molybdenum is the exception, becoming more available at higher pH.

- Organic Matter: Low organic matter reduces micronutrient retention and cycling.

- Soil Texture: Sandy soils are prone to deficiencies due to leaching and naturally lower micronutrient content.

- Soil Moisture: Both waterlogged and drought conditions can limit micronutrient uptake.

- Temperature: Cold soils often reduce availability through decreased root activity and slower biological processes.

- Nutrient Interactions: Excessive levels of phosphorus can inhibit zinc and iron uptake; high calcium levels can interfere with magnesium uptake.

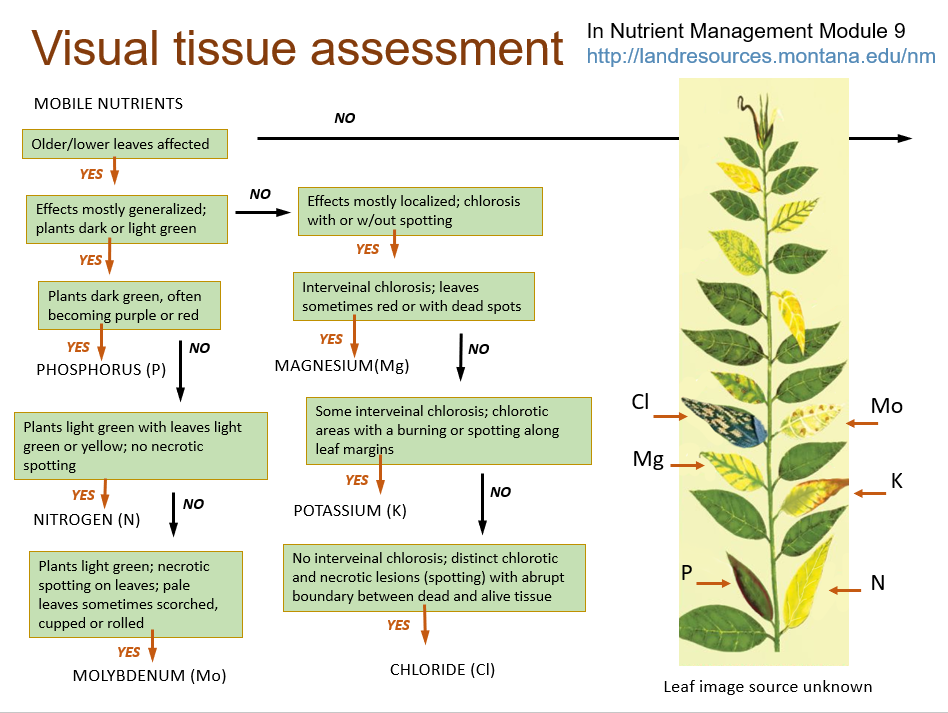

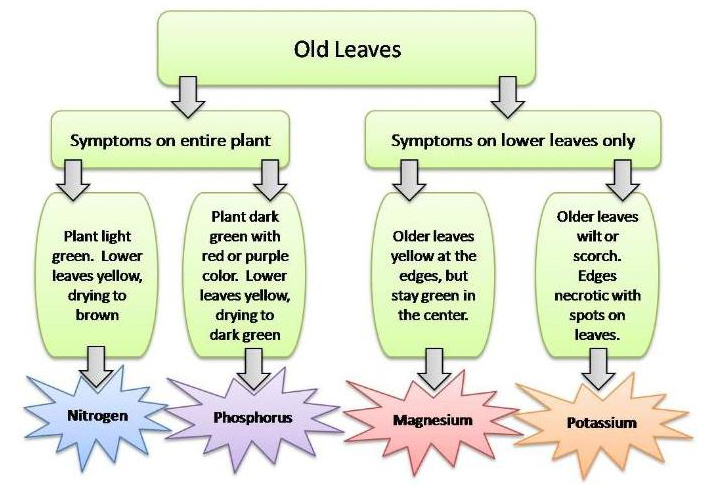

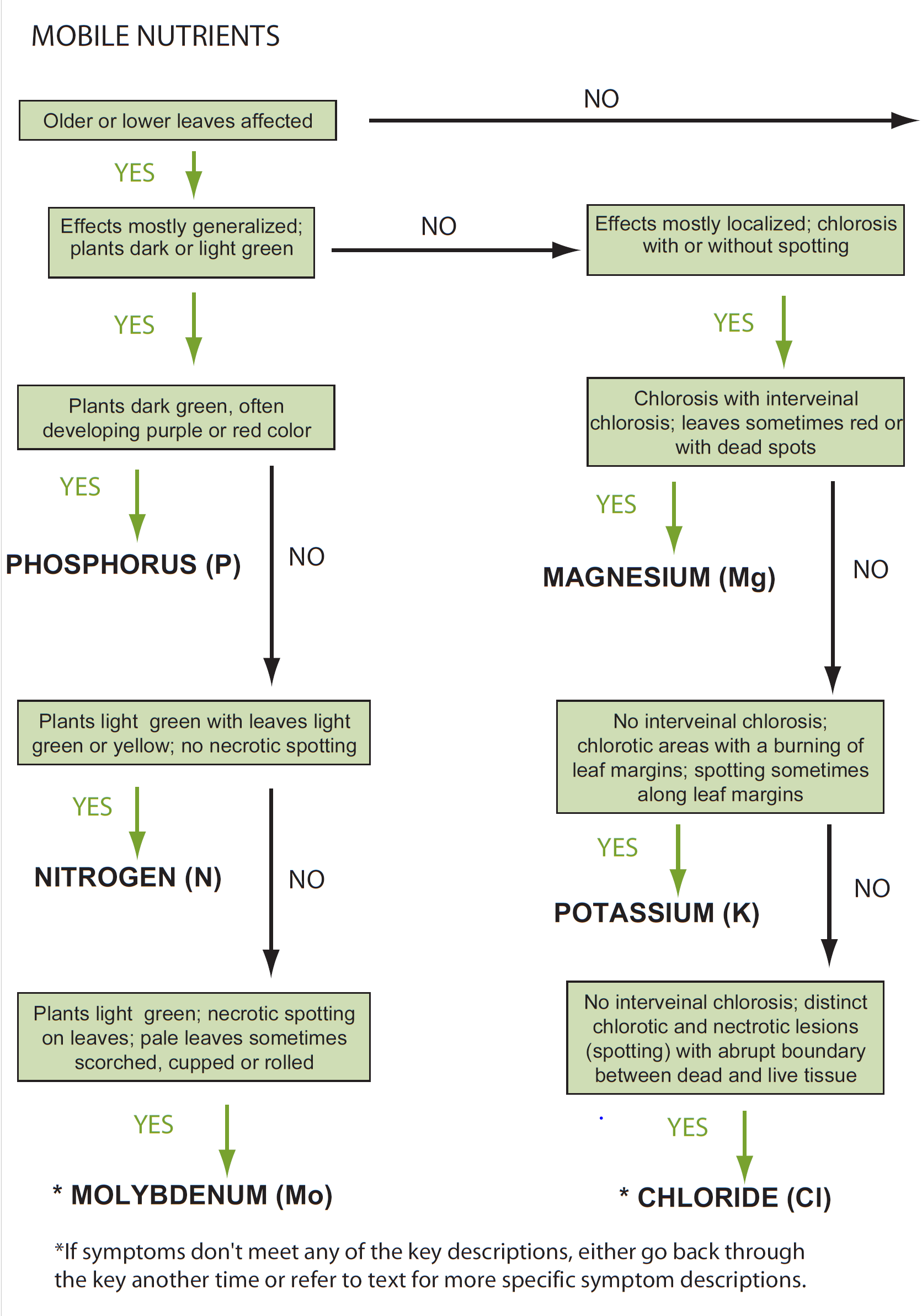

The Art of Visual Diagnosis

Visual diagnosis of nutrient deficiencies is a skill that combines scientific understanding with careful observation. Before diving into specific micronutrient symptoms, it's important to understand some foundational principles:

Key Diagnostic Principles

- Pattern of Appearance:

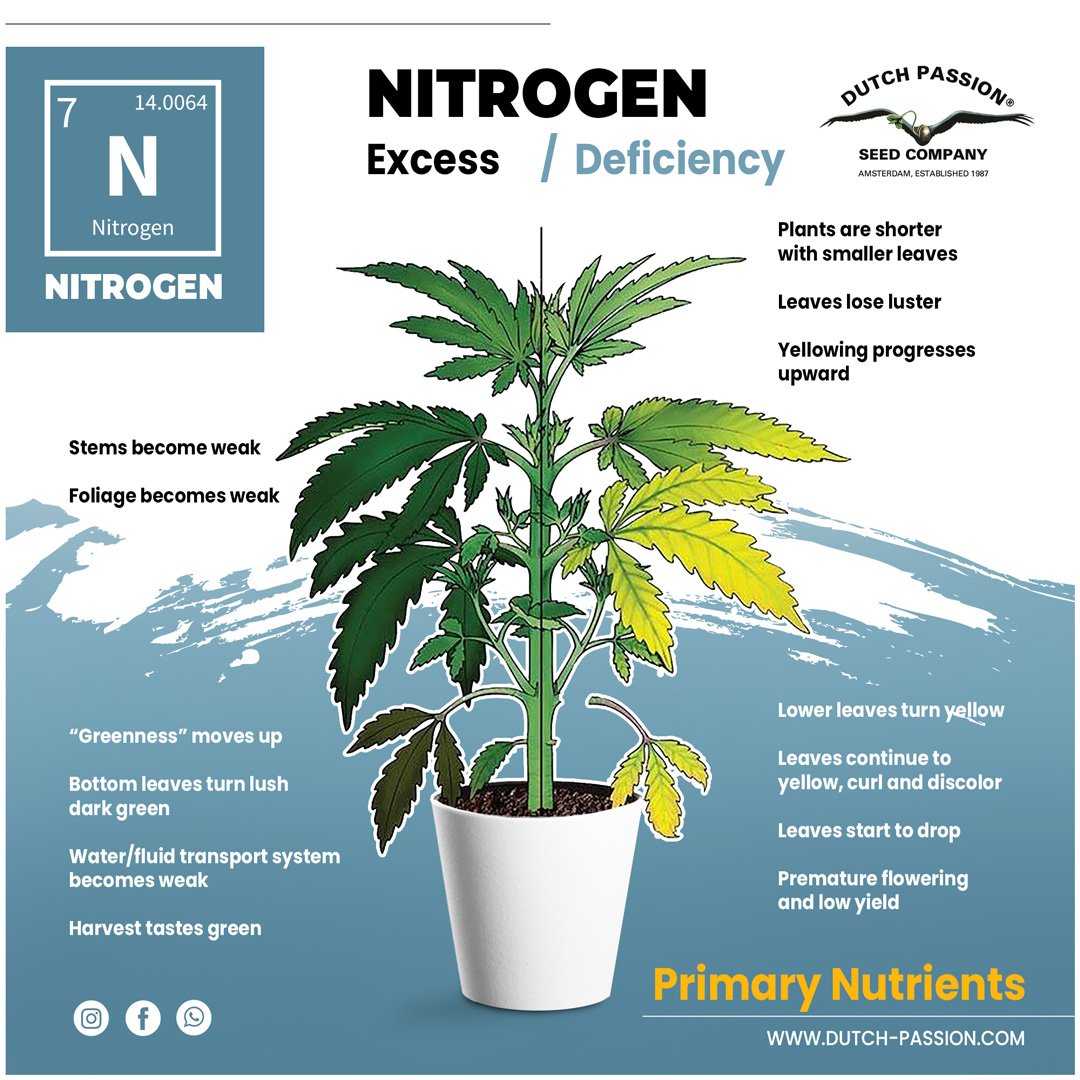

- Immobile nutrients (most micronutrients): Symptoms appear first on young leaves and growing points

- Mobile nutrients (N, P, K, Mg): Symptoms appear first on older, lower leaves

- Distribution on the Plant: Is the issue widespread or localized to certain parts?

- Distribution in the Field: Random spots, edges, or patterns can indicate different issues

- Progression: How quickly symptoms develop and spread

- Timing: When symptoms appear during the growing season

Common Symptom Categories

- Chlorosis: Yellowing due to reduced chlorophyll

- Interveinal Chlorosis: Yellowing between veins while veins remain green

- Necrosis: Dead tissue appearing as brown, black, or dry areas

- Stunting: Reduced growth of entire plant or specific parts

- Malformation: Unusual shapes or development of plant parts

Confirmation Methods

While visual symptoms provide valuable clues, confirmation should involve:

- Soil Testing: To determine available nutrient levels and pH

- Tissue Testing: To measure actual nutrient concentrations in plant tissues

- Field Trials: Small test areas with corrective treatments

Note: Many environmental stresses, pests, and diseases can mimic nutrient deficiencies. Always consider multiple diagnostic approaches before implementing correction strategies.

Zinc Deficiency

Zinc deficiency is one of the most widespread micronutrient issues affecting crop production worldwide, particularly in calcareous, high-pH, and intensively cultivated soils.

Visual Symptoms:

- "Little leaf" syndrome - dramatically reduced leaf size

- Interveinal chlorosis with mottling on young leaves

- Shortened internodes leading to rosette appearance

- Wavy leaf margins and upward cupping

- Bronzing or reddish-brown spots on lower leaves

Correction Strategies:

- Soil application: 5-10 lbs/acre zinc sulfate

- Foliar spray: 0.5% zinc sulfate solution or chelated zinc products

- Seed treatments containing zinc

- Band application near seed row for efficient uptake

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Corn: White to yellowish bands on either side of the leaf midrib; stunting; broad white stripes

- Fruit Trees: "Little leaf" condition, terminal dieback, rosetting of leaves

- Beans: Bronzing and mottled yellowing of older leaves

- Rice: "Khaira disease" - bronzing of lower leaves and stunted plants

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- High soil pH (>7.0)

- High phosphorus levels in soil

- Cold, wet soil conditions

- Sandy soils with low organic matter

- Heavily eroded soils where topsoil has been removed

Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency is characterized by its distinctive yellowing pattern and is particularly common in alkaline and calcareous soils. Despite often being abundant in soil, iron availability to plants is highly dependent on soil chemistry.

Visual Symptoms:

- Pronounced interveinal chlorosis on young leaves

- Distinctive "Christmas tree" pattern where veins remain green

- Leaf edges and tips may remain green longer than interveinal areas

- Severe cases lead to completely bleached leaves and necrosis

- New leaves emerge pale yellow to almost white

Correction Strategies:

- Foliar application of iron chelates (most effective method)

- Soil application of iron chelates (EDDHA forms work best in high pH soils)

- Acidification of root zone in container production

- Iron sulfate applications combined with organic matter

- In severe cases, consider acidifying irrigation water

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Soybeans: Severe interveinal chlorosis, stunted growth

- Fruit Trees: Yellowing between veins while veins remain green; reduced fruit set

- Berries: Pale new growth with green venation; reduced vigor

- Ornamentals: Especially pronounced in acid-loving plants (azaleas, rhododendrons) when grown in alkaline soils

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- Alkaline soils (pH >7.5)

- Calcareous soils high in free lime

- Cool, wet soil conditions

- Poorly aerated or compacted soils

- High phosphorus levels

- Excessive irrigation or heavy rainfall that saturates soil

Special Considerations

Iron deficiency is notoriously difficult to correct with soil applications in high pH soils. Chelated forms (especially EDDHA) are more effective but more expensive. For perennial crops in calcareous soils, consider iron-efficient varieties or rootstocks as a long-term solution.

Manganese Deficiency

Manganese deficiency is commonly confused with iron deficiency due to similar chlorosis patterns, but careful observation reveals distinctive differences that can guide proper correction.

Visual Symptoms:

- Interveinal chlorosis with small green veins creating a checkered or speckled appearance

- Gray or tan necrotic spots often develop within chlorotic areas

- Less distinctive vein pattern than iron deficiency

- Typically appears on middle leaves first, then young leaves

- Leaves may appear limp or droopy despite adequate water

Correction Strategies:

- Foliar application of manganese sulfate (1-2 lbs/acre)

- Soil application of manganese sulfate (20-30 lbs/acre)

- Chelated manganese products for foliar application

- Acidifying fertilizers to increase availability in high pH soils

- Multiple foliar applications often needed during growing season

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Soybeans: Interveinal chlorosis with small distinct green veins; yellow-white mottling

- Oats: "Gray speck" disease - gray necrotic spots within chlorotic areas

- Wheat: Yellow spots that elongate and form streaks between veins

- Citrus: Mottled chlorotic areas between veins with green banding along veins

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- High soil pH (>6.5)

- Highly leached, weathered soils

- Excessively drained sandy soils

- Soils high in organic matter (especially peat and muck soils)

- Cool, wet conditions that slow microbial activity

- Soils with high iron content (competitive inhibition)

Distinguishing from Iron Deficiency

While both iron and manganese deficiency cause interveinal chlorosis, manganese deficiency typically shows:

- Smaller green veins creating a more checkered pattern

- Necrotic spots within chlorotic areas

- Often affects middle leaves first rather than newest growth

- Less severe bleaching effect than iron deficiency

Copper Deficiency

Though less common than other micronutrient deficiencies in many regions, copper deficiency can have dramatic effects on crop development, particularly in cereal grains and on organic soils.

Visual Symptoms:

- Stunted growth with terminal dieback

- Young leaves appear permanently wilted or limp

- Twisted or distorted leaf blades and stem growth

- Bleached appearance of young growth

- Delayed flowering and reduced seed formation

- "Pig-tailing" or curling of leaf tips in cereal crops

Correction Strategies:

- Soil application of copper sulfate (10-20 lbs/acre)

- Foliar application of copper sulfate (0.1-0.5% solution)

- Chelated copper products for both soil and foliar applications

- Copper-containing fungicides provide dual protection and nutrition

- For organic soils, higher rates may be needed due to binding

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Small Grains: Twisted, curled leaf tips; bleached appearance; empty grain heads; lodging

- Corn: Yellow or white streaking of young leaves; limp appearance

- Onions: Thin, pale leaves that wither at the tips; bulbs lack flavor and store poorly

- Fruit Trees: Dieback of terminals; sparse foliage; gum exudation; small, poorly colored fruit

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- Organic soils (peat and muck)

- Highly leached sandy soils

- Soils with pH above 7.5

- Soils with unusually high nitrogen levels

- Newly reclaimed land that was previously waterlogged

- Soils with high organic matter content that binds copper

Economic Impact

Copper deficiency can be particularly devastating because it affects both yield and quality. In cereal crops, severe deficiency can result in completely empty grain heads despite apparently healthy vegetative growth early in the season. In fruit production, both size and flavor are diminished, with poor storage characteristics.

Boron Deficiency

Boron is distinctive among micronutrients due to its narrow range between deficiency and toxicity, making accurate diagnosis and careful correction essential.

Visual Symptoms:

- Death of growing points (apical meristems)

- Thickened, brittle, or curled leaves

- Discolored, cracked, or corky stems, fruits, and roots

- Stunted, bushy appearance due to loss of dominance

- Flower abortion and poor fruit set

- Hollow stems or fruits (hollow heart)

Correction Strategies:

- Soil application of borax or solubor (0.5-3 lbs B/acre depending on crop sensitivity)

- Foliar sprays of solubor (0.1-0.5 lbs B/acre)

- Borated fertilizer blends

- CAUTION: Narrow range between deficiency and toxicity - precise application is critical

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Alfalfa: Yellow or reddish leaves; shortened internodes; rosetting

- Brassicas: Hollow stem; brown heart of rutabagas and turnips

- Celery: Cracked stems with brown discoloration

- Apples: Internal cork; misshapen fruit; cracked fruit

- Root Crops: Brown heart; internal discoloration; cracking

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- Sandy, acid soils with low organic matter

- Soils with pH above 6.5

- Drought conditions (limited movement through soil solution)

- Soils with high calcium content

- Recently limed soils

- Leaching from heavy rainfall or irrigation

Special Considerations

Boron has the narrowest range between deficiency and toxicity among all plant nutrients. Over-application can easily lead to toxicity symptoms, including leaf margin yellowing, necrotic spots, and premature leaf drop. Different crops have dramatically different boron requirements:

- High Boron Need: Alfalfa, clover, brassicas, sugar beets

- Medium Boron Need: Apples, carrots, celery, potatoes

- Low Boron Need: Cereals, corn, grasses, soybeans

Always adjust application rates according to crop sensitivity.

Molybdenum Deficiency

Molybdenum is required in the smallest quantities of all essential nutrients, yet its deficiency can have profound effects, particularly on nitrogen metabolism in legumes and other crops.

Visual Symptoms:

- Pale green to yellow leaves with interveinal and marginal chlorosis

- Leaf mottling and curling of margins

- Stunted growth and poor flowering

- In legumes: symptoms resemble nitrogen deficiency

- In brassicas: "whiptail" - narrow leaf blades with twisted appearance

- Reduced nodulation in legumes

Correction Strategies:

- Soil application of sodium molybdate (1-2 oz Mo/acre)

- Foliar spray of sodium or ammonium molybdate (0.5-1 oz Mo/acre)

- Seed treatment (especially for legumes) with molybdenum solution

- Lime application to raise soil pH (increases Mo availability)

Crop-Specific Symptoms

- Legumes: Nitrogen deficiency symptoms despite nodulation; stunted growth; poor seed set

- Brassicas: "Whiptail" with narrow, distorted leaves; severe stunting; lack of head formation

- Citrus: Yellow spot disease; mottled chlorosis; small, low-quality fruit

- Lettuce: "Lettuce yellows" - interveinal chlorosis followed by necrosis

Environmental Conditions Favoring Deficiency

- Acid soils (pH below 6.0)

- Highly weathered, leached soils

- Soils high in iron oxides

- Sandy soils low in organic matter

- Soils high in sulfate ions (competitive inhibition)

Unique Aspects

Unlike most micronutrients, molybdenum becomes more available as soil pH increases. Liming acid soils is often the most economical way to address molybdenum deficiency. Molybdenum is also unique in that extremely small quantities can correct deficiency - often measured in ounces rather than pounds per acre.

Comparative Diagnosis Guide

When symptoms are unclear or appear to overlap, use this comparative guide to help narrow down the likely deficiency:

| Feature | Zinc (Zn) | Iron (Fe) | Manganese (Mn) | Copper (Cu) | Boron (B) | Molybdenum (Mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Location | New leaves | New leaves | Middle leaves | Young and expanding leaves | Growing points | Lower to middle leaves |

| Chlorosis Pattern | Interveinal with mottling | Interveinal with green veins | Interveinal with checkered pattern | General pale color | Rarely chlorotic | General yellowing |

| Distinctive Feature | "Little leaf"; rosetting | Christmas tree pattern | Speckled necrotic spots | Twisted new growth | Death of growing points | Whiptail in brassicas |

| Effect on Stems | Shortened internodes | Minimal effect | Minimal effect | Withering of tips | Cracking, hollow, corky | Minimal effect |

| Effect on Fruits | Small, misshapen | Poor coloration | Poor development | Small, poor quality | Cracked, corky, hollow | Reduced set |

| Most Prone Soil pH | >7.0 | >7.5 | >6.5 | >7.5 | >6.5 | <6.0 |

Confirmation Testing

While visual diagnosis is valuable for preliminary identification, laboratory testing provides confirmation:

| Micronutrient | Soil Test Critical Level | Tissue Test Sufficient Range | Test Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn) | 1.0-1.5 ppm (DTPA extract) | 20-100 ppm | DTPA extraction |

| Iron (Fe) | 4.5-10 ppm (DTPA extract) | 50-250 ppm | DTPA extraction |

| Manganese (Mn) | 1.0-5.0 ppm (DTPA extract) | 20-300 ppm | DTPA extraction |

| Copper (Cu) | 0.2-0.5 ppm (DTPA extract) | 5-20 ppm | DTPA extraction |

| Boron (B) | 0.5-1.0 ppm (hot water extract) | 20-100 ppm | Hot water extraction |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.1-0.3 ppm (ammonium oxalate) | 0.5-5 ppm | Ammonium oxalate |

Note: Sufficient tissue ranges vary considerably by crop and plant part sampled. Values provided are general guidelines only.

Correction Strategies

Once a micronutrient deficiency has been identified, several application strategies can be employed, each with advantages in different situations:

Soil Applications

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcast Application | Uniform distribution; longer-term correction | Higher rates needed; slower response; potential fixation | Pre-plant correction; long-term prevention |

| Band Application | Concentrated near roots; reduced fixation; lower rates | Limited soil volume treated; requires specialized equipment | Row crops at planting; efficient use of materials |

| Fertigation | Uniform distribution; can time with crop needs | Requires irrigation system; potential precipitation issues | High-value crops with drip irrigation |

Foliar Applications

| Product Type | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfate Forms | Economical; readily available | Potential phytotoxicity; narrow pH range for effectiveness | Emergency correction; crops not sensitive to leaf burn |

| Chelated Forms | Lower phytotoxicity; better leaf penetration | More expensive; specific pH requirements | High-value crops; sensitive plant tissues |

| Nitrate Forms | Good solubility; rapid uptake | May stimulate excessive growth; more expensive | Quick correction during active growth |

Formulation Selection Guide

| Micronutrient | Common Forms | Typical Rates (Soil) | Typical Rates (Foliar) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn) | Zinc sulfate; Zinc EDTA; Zinc oxide | 5-15 lbs/acre | 0.5-1.5 lbs/acre |

| Iron (Fe) | Iron sulfate; Iron EDDHA; Iron DTPA | 20-50 lbs/acre (sulfate); 2-10 lbs/acre (chelate) | 1-2 lbs/acre |

| Manganese (Mn) | Manganese sulfate; Manganese oxide; Manganese chelates | 10-30 lbs/acre | 1-2 lbs/acre |

| Copper (Cu) | Copper sulfate; Copper oxide; Copper chelates | 5-20 lbs/acre | 0.25-1.0 lbs/acre |

| Boron (B) | Borax; Solubor; Boric acid | 1-3 lbs B/acre | 0.1-0.5 lbs B/acre |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | Sodium molybdate; Ammonium molybdate | 1-2 oz Mo/acre | 0.5-1 oz Mo/acre |

Application Timing

For maximum effectiveness, consider these timing principles:

- Soil Applications: Apply weeks before peak demand; incorporate when possible

- Foliar Applications: Apply early in the day when stomata are open and humidity is high

- Growth Stage Timing: Target applications just before critical growth stages (early vegetative for most micronutrients)

- Multiple Applications: Often more effective than single large application, especially for foliar sprays

Preventative Measures

The most effective approach to micronutrient management is prevention rather than correction of deficiencies once they appear. Implement these strategies to maintain optimal micronutrient levels:

Soil Management Practices

- pH Management: Maintain soil pH in the 6.0-7.0 range for optimal micronutrient availability when possible

- Organic Matter: Increase organic matter through cover crops, crop residues, and organic amendments

- Balanced Fertilization: Avoid excessive phosphorus applications that can induce zinc and iron deficiencies

- Soil Testing: Conduct comprehensive soil tests every 2-3 years that include micronutrients

- Reduced Tillage: Minimize soil disturbance to maintain biological activity and nutrient cycling

Crop Selection and Management

- Variety Selection: Choose varieties or rootstocks with greater efficiency in micronutrient uptake

- Crop Rotation: Include diverse crops with different nutrient requirements and root patterns

- Companion Planting: Some plant combinations enhance micronutrient availability

- Tissue Testing: Monitor plant nutrient status through regular tissue testing

Fertilizer Strategies

- Micronutrient-Enriched Fertilizers: Use fertilizer blends that include micronutrients

- Maintenance Applications: Apply small amounts regularly rather than corrective doses

- Seed Treatments: Consider micronutrient-treated seed, especially for zinc and molybdenum

- Balanced Approach: Ensure all nutrients are in proper proportion to avoid antagonistic effects

Long-term Soil Building

The most sustainable approach to micronutrient management involves building soil health:

- Increase biological activity through minimal disturbance and organic inputs

- Enhance mycorrhizal associations that improve micronutrient uptake

- Improve soil structure for better root exploration and nutrient interception

- Use cover crops and green manures to recycle nutrients and prevent leaching

These preventative approaches not only reduce the likelihood of micronutrient deficiencies but also contribute to overall soil health and resilience of the agricultural system.

Conclusion

Micronutrient deficiencies can significantly impact crop yields and quality, often going unrecognized until substantial damage has occurred. By developing the skills to visually identify these deficiencies, confirming them with appropriate testing, and implementing targeted correction strategies, farmers can maintain optimal crop nutrition and productivity.

Remember that micronutrients function as part of a balanced nutritional system. Addressing deficiencies should be approached holistically, considering not just the immediate symptom but the underlying soil conditions, crop requirements, and management practices that influence nutrient availability.

The most sustainable approach combines careful observation, regular soil and tissue testing, preventative applications based on crop needs, and long-term soil-building practices. By integrating these strategies, farmers can ensure their crops receive the full spectrum of nutrients needed for optimal growth, resilience to stress, and high-quality production.